It had been known for many years that a “bone cellar”, as it was called in village parlance, existed under the Michaelskapelle. So in former times it was quite common among the young boys to crawl into this cellar through a hole at the northern end. As a test of courage, bones or parts of bones were occasionally taken outside. After a thorough examination, however, these bones were soon thrown back into the cellar.

It was known from stories that in the past it was customary, when reburying graves, to remove the bones of the dead previously buried in these graves from the emptied graves and deposit them in the “bone cellar”. This was especially necessary in order to be able to use the cemetery space again and again without having to designate new cemetery areas in the village. In addition, it used to be customary to carry out burials as close as possible to the church.

The custom of moving the bones to a separate secondary burial room eventually fell asleep. This led to the gradual forgetting of the custom and place of bone storage. Today it is no longer possible to trace exactly when the last bones were brought to the charnel house, but it is assumed that the last transfers of bones to the ossuary took place somewhere in the 19th century. However, some bones were still thrown into the opening of the cellar until the end of the use of the cemetery at the church around 1960.

During the renovation work on St. Michael’s Chapel in 2010, the Bone Cellar was remembered and a scientific study of this cellar, the Ossuary, began.

It was soon discovered that this ossuary, also known as the “Karner” or scientific ossuary, was an older building than, for example, St Michael’s Chapel and charnel house in Limburg.

The archaeological investigations were conducted by Martino La Torre. The investigation was initiated by Prof. Dr. K. Löffelholz, among others, who was also actively involved in the archaeological investigations and excavations between 1955/57 as a student.

The cellar filling was up to the level of the upper edge of the present entrance door. The cellar was completely cleared out in months of work. In the cleared out material, besides many bones, stoneware shards and porcelain were found. The use of the”Karner” could thus be traced back to around the 19th century. According to the archival documents of the diocesan archive, the lower vault is said to have been inaccessible shortly thereafter (see also Hessenarchäologie, 2011, La Torre, Bauarchäologische Untersuchungen des Karners der Michaelskapelle an der St. Lubentiuskirche in Dietkirchen-Ein Arbeitsbericht).

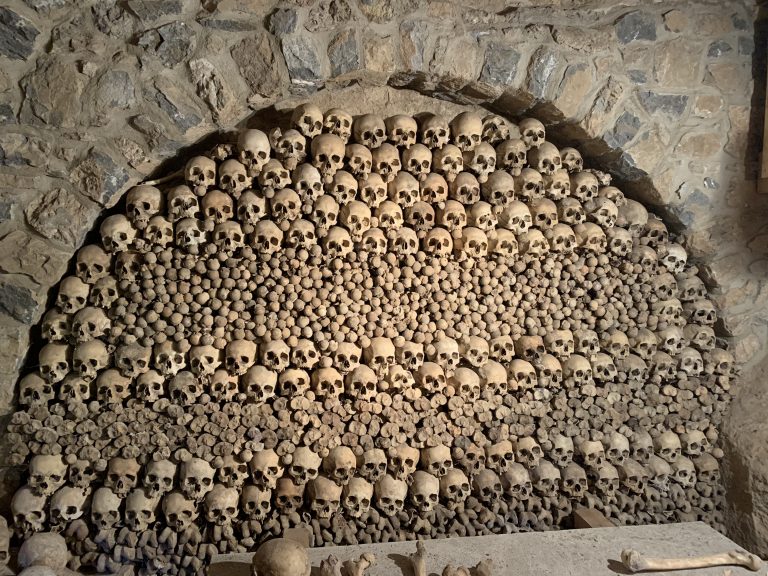

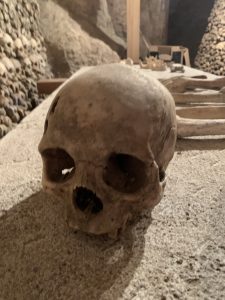

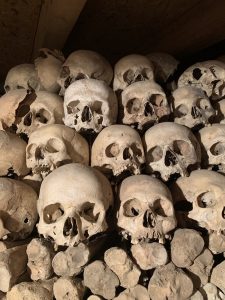

On the south wall of the “Karner”, a bone wall made of skulls and other bones has been left in the original. This wall has the following dimensions: 2.60 meters long – 1.40 meters high and 1 meter thick. As this is an extremely rare find of an original layer of bone material, it is to remain in the original and is only available for locally to proceed investigations.

Based on the material found, it can be assumed that the ossuary was

used from around 1475 until the beginning of the 19th century.

The special thing about the ossuary in Dietkirchen is that it was not

cleared out and refilled with new bones during the last centuries, but

remained in its original condition from the first use until the end of

its useful life.

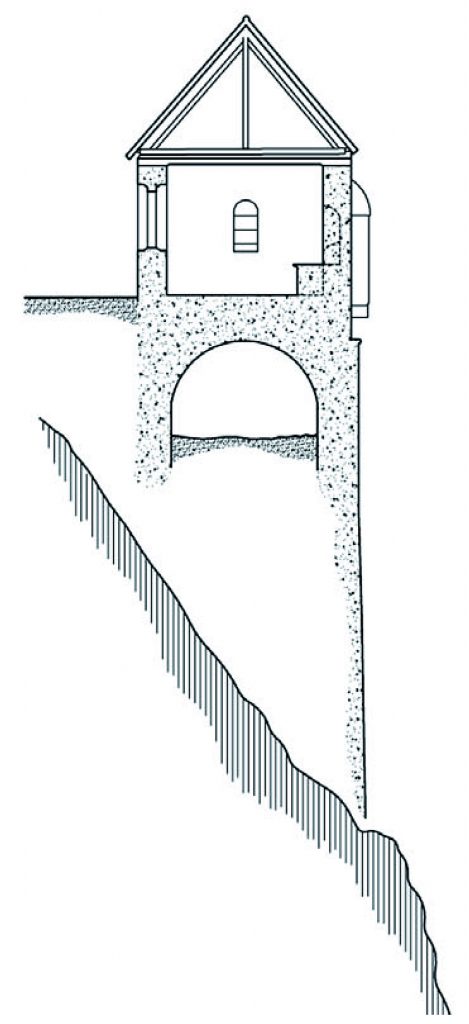

During the structural investigations of the crypt it was discovered

that it was a cellar covered with a barrel vault and about 5 meters

high. The ceiling vault was built of quarry stones over a formwork of

billet wood. The structural investigations suggest that the actual floor

extends much further down.

From the sectional view of the chapel and charnel house, one can see

that the outer wall extends very deeply down the rock towards the Lahn.

Further investigations in the future could certainly bring further

interesting details to light.

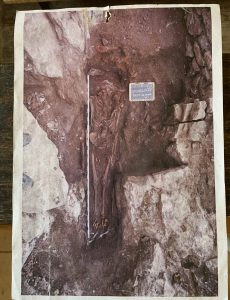

During the work, a skeleton was also discovered in front of the

entrance to the Karner at a depth of about 4 metres, which could be

attributed to the Carolingian period (8th – 9th century), i.e. over 1000

years old.

About 15 centimetres above this skeleton were found the remains of

another deceased. However, this skeleton was no longer completely

present.

The skeleton found at a depth of 4 meters is the completely preserved

skeleton of a man about 1.80 meters tall. The scientific investigations

were able to find out a lot about the man’s state of health. So he

probably became relatively old. He suffered from bladder stones.

Furthermore he had a healed fracture of his humerus. He must have been

plagued by severe back pain due to two intertwined vertebrae. A hand

heavily infested with gout probably indicates a prosperous overall

situation and good nutrition.

It is presumed that this complete skeleton could possibly be a

spiritual or also a worldly dignitary, as only such people usually

received permission to be buried in or at churches. Normal people were

buried in general cemeteries.

The person of the incompletely found skeleton is presumed to be a successor in office or relative of the complete skeleton found in the deeper layer.

The bones were taken in about 120 moving boxes to the Anthropological Institute of the University of Giessen for further examination. There, all 736 skull bones (or their fragments) and all 720 thigh bones were examined scientifically forensically. Dr. Franziska Holz played a special role in this process. In 2015, she completed her doctoral thesis entitled “Forensic Anthropological Investigations at the Carner Collective of the Michaelskapelle in Limburg-Dietkirchen with a focus on cranial trauma” and thus obtained her doctorate.

Her examinations of the cranial bones revealed that 52% of the deceased were male, 31% female and 8% indifferent. All skulls not clearly classifiable as adult skulls were grouped into a grouping of children and adolescents, which was determined to be 9%. In determining the age at death, she determined that every tenth, i.e. 10.7%, died before the age of 21. 25.8% died between the ages of 21 and 40. 33.7% died between the ages of 41 and 60. 20.6% reached the age of 60. For 9.2% it was not possible to determine the age at which they died.

It was determined that about 37.4% of the women died between the ages of 20 and 40. Only 24.2% of men in the same age group died. This suggests that the cause of the increased mortality of women was the consequences of pregnancies and births.

Calculations resulted in the following body sizes. The smallest man had a height of 153.9 cm +/- 3.3 cm, the largest was 183.4 cm +/- 3.3 cm tall. The average male body height was 166.0 cm +/- 3.3 cm.

The average height of the women was 152.9 cm +/- 3.3 cm. The smallest woman was 143.5 cm +/- 3.3 cm, the largest woman was 165.8 cm +/- 3.3 cm.

It was also found that a great many skulls had perimortem injuries, i.e. injuries that occurred directly at the time of death. Two thirds of these injuries were caused by blunt force (stone, club, tools or surfaces), one third by punctual force, i.e. most likely by bullets, lances, arrows or spears or similar. Some skulls were also injured by sword, knife, axe or hatchet.

It has been proven that 65% of all perimortem cranial injuries were almost certainly the result of violent conflicts directly person against person.

The teeth of the skull were also subjected to close examination. Dental caries was found in 28.5% of all teeth examined.

After the investigations were completed, the skulls and bones were completely returned to Dietkirchen.

Here they were piled up by Dr. Franziska Holz and Dr. Gabriel Hefele (former director of the Diocesan Museum and art historian) in a new and very reverent way in a side niche and below the newly created visitor’s platform in the Karner, which had been prepared in the meantime.

A memorial stone was found during the clearing work in the Karner.

Original:

1724 den 29. Feb:

Hat der Ehrsamme Fridrich Burggraff und Christina ehele(.)

sentschöffen zu dehrn diesen grabstein

vor sich und die seinige zu ehren der

Allerheiligsten dreÿfaltigkeit hirher

auffrichten lassen, requiescant in

Pace. Amen.

Its inscription reads:

1724 Feb. 29:

the Honorable Fridrich

Burggraff and Christina spouses

sentschöffen at dehrn

erected this gravestone here

for himself and his wife to honor the

Most Holy Trinity, requiescant in

Pace. Amen.

Sources:

Hessenarchäologie, 2016, Franziska Holz, Christoph G. Birngruber, Martino La Torre, Marcel A. Verhoff, Das Beinhaus der ehemaligen Stiftskirche St. Lubentius in Dietkirchen

Hessenarchäologie, 2016, Franziska Holz, Christoph G. Birngruber, Marcel A. Verhoff, Auf den Zahn gefühlt – odontologische Untersuchungen an Schädeln des Beinhauses von St. Lubentius

Lecture from Prof. Klaus Nohlen 2012

Pictures

© Ludwig Ries