„View of Dietkirchen, 1862“,

in: Historische Ortsansichten:

https://www.lagis-hessen.de/de/subjects/idrec/sn/oa/id/574

(status: 10.4.2007)

History of the village of Dietkirchen

Prehistoric times

The history of the place Dietkirchen certainly goes far back in time. From the time of the Germanic up to today there is a knowledge about a pagan cult place at the top of the lime rock in Dietkirchen. A first view of this exposed single rock directly suggest that this is a special place. From far away you can feel an energy that this rock holds and radiates. The knowledge of a pagan place of worship was reinforced through the excavations that were carried out in the middle of the 1950s in connection with the installation of hot water heating in 1955/1957 and in the summer of 1965 in the church of St. Lubentius. On the basis of fracments of broken ceramic it can be demonstrated that this rock was populated and used since the Neolithic period which was between 5000 and 2200 BC. This settlement was continued in the urn field period (Bronze age) and the Hallstatt period and the Latene period (Iron age). See also short report by Karl Wurm in Wilhelm Schäfer: Die Baugeschichte der Stiftskirche St. Lubentius zu Dietkirchen im Lahntale, 1966, self published by the Historical Commission for Nassau. Wurm also assumed that the hill was possibly fortified in the early period and could only be reached via a narrow path. In his preliminary report on the final excavations in the summer of 1965, see the article entitled “Vorbericht über die Abschlußgrabung unter der Stiftskirche von Dietkirchen/Lahn im Sommer 1965” in “Fundberichte aus Hessen, 5.u. 6. Jahrgang, 1965/66, Verlag Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn”, reports K. Wurm also of a skeleton find, which however cannot be assigned to a certain time period, as well as of numerous fragments found, which are attributable to the urn field culture. Furthermore, a stone hatchet and another small sharpened stone hatchet was found together with various animal bones. An examination of these animal bones by institutions of the University of Mainz should provide information about whether the bone finds are a Neolithic hunting camp or a victim’s site. Unfortunately, the author of this website text has so far not been able to find a literary source with the results of these studies.

Jurisdiction

It is often shown in various literature sources that this place on the rock was also called grove and that a court was held here. Based on the findings from 1955/57 and the research results of K. Wurm, this cannot be absolutely agreed. Nevertheless, the literature gives hints that the early Germanic Thing, which was both the people’s assembly and the judicial assembly, is said to potentially could have been held here. Popular thing places are said to have been tribal sanctuaries, which are usually located in groves or on elevations. As a result, it is certainly not entirely ruled out that meetings may have taken place on the rock and thus also court hearings.

The jurisdiction continues to play an important role in Dietkirchen. The Reckenforst, the place of judicial assembly of the Count of Diez, was in the immediate vicinity. He is mentioned in documents in the Codex Oculus Memoriae of the Eberbach Cistercians as early as 1217. There it is said that around 1190 a couple from Niederhadamar transferred their agricultural estate to the monastery. This is said to have happened at a public court hearing, which was also called Landesthing (landtgedinge). Count Gerhard von Diez is said to have presided over this negotiation himself in the Reckenforst (in reckenvorst). The meeting place itself was also called THING. See also the treatise “Reckenforst” by Peter Paul Schweitzer. The Limburg chronicler Tileman Elhen von Wolfhagen also reports in his chronicle about a negotiation on the Reckenforst. In 1367, a Frei von Dehrn, Friedrich Frei von Dehrn, stabbed Johan, the Count’s son from Diez. Friedrich was caught in Dehrn and taken to Diez. Gerhard, the brother of the stabbed, then called a court on the Reckenforst, where the death sentence against the Frei von Dehrn was passed and his head was cut off. Original text from the chronicle: “Der selbe Frige hiß Frederich, ein strenge ritter von funfzig jaren, unde was ein recht frige geboren von allen sinen vir annichen. Unde wart he gefangen zu Derne uf dem huise unde wart gefurt gen Ditze. Unde greb Gerhard, junghern Johans bruder, det ein lantgerichte bescheiden zu Reckenforst, unde wart dem vurgenanten Frigen sin heupt abegeslagen unde wart begraben von stunt gen Limpurg zu den barfußen.”.

drawn map from Conrad Forth, 1696,

Map collection in the city archive of Limburg,

“I” means the location of Reckenforst

First documentary designation of Dietkirchen

The oldest mention of Dietkirchen known to us can be found in one certificate of a gift from a Nentershausen clergyman 841 to the Lubentiusstift in Dietkirchen. For example, it says in a treatise by Pastor Ferdinand Ebert, Oberelbert in the yearbook for the Diocese of Limburg from 1958 that in one of Brower-Masen (Jesuit and Historian 1599-1617) in his book Metropolis mentioned certificate of the Deacon Adelbert, that this Adelbert “famulus et coenobita” (servant and monk) of St. Lubentius on 13. May 841 his “cella” at Nentershausen bequeathed to the “manosteriolum” of St. Lubentius zu Dietkirchen.

Christianization and St. Lubentius

Christianization is a turning point in the history of the village. According to today’s knowledge, the Christian missionaries came from the Neuwieder Becken into the Lahn area and this in the 5th / 6th century.

As the excavations from 1955-57 in St. Lubentius church were able to prove a simple stone church around 730, it can actually be assumed that before the construction of this stone church there had been Christian activities on the rock on which the church was built. In the early missionaries, pagan sites were very often overlaid by christian church buildings.

The same will have happened to the Germanic sanctuary in Dietkirchen, which was supposed to be dedicated to the highest Germanic god Tit, who was also called Thuit or Ziu. It is believed that a very first Christian site may have existed at the site of the Stefanus chapel, which was demolished in 1838. In early Christian times, it was well practiced by missionaries to build pagan squares with churches or chapels dedicated to St. Michael or St. Stefan.

Lubentius, the patron saint of Dietkirchen, is said to have lived in the 4th century AD and have died AD 360. His main area of activity was in Kobern on the Moselle.

According to oral tradition, which is based on a called legendarily reported transmission of the body of St. Lubentius 839, Lubentius is said to have been a missionary in Dietkirchen. This is unlikely, but not out of the question, since the Roman imperial borders were overrun AD 352 and 355 and practically destroyed by the Alemanni, Franconia and Saxony. At that time, Lubentius was a priest in Kobern. So it is quite possible that there is a historical truth behind the legends: Lubentius was in Dietkirchen, although it actually seems to be largely undisputed in science that St. Lubentius, who was venerated in Dietkirchen, probably did not missionate and preach in Dietkirchen himself. From a scientific historical point of view, almost everyone tends to have the fact that St. Lubentius may have existed in historical form, but that his personal work in Dietkirchen was unlikely to be realistic.

There is good reason to believe that between AD 836 – 840 the bones of St. Lubentius von Kobern on the Moselle were transferred to Dietkirchen. February 6 is given as the translation date (date of the transfer of the bones) in all literature sources. Up to date, the translation legend has been analyzed and researched by many historians. All of her judgments come to the conclusion that there is little or no truth to this legend itself. It is still open, according to all interpretations, why Dietkirchen was chosen as the residence of a large part of the relics of St. Lubentius. Most likely the thesis appears that the Archdiocese of Trier wanted to establish a church base on the right bank of the Rhine with the Translatio, because according to the translation legend high dignitaries were named as contributors to the Translatio, e.g. the Archbishop of Cologne. It is also possible that Trier also wanted to manifest his claim to the Lahn area to the Archdiocese of Mainz.

St. Lubentius

Joachim Schäfer – https://www.heiligenlexikon.de

Relic base for the bust of St. Lubentius in gold-plated brass with rock crystal and ruby in 2016

Luthmer volume III page 157

Dietkirchen Reliquary of Saint Lubentius

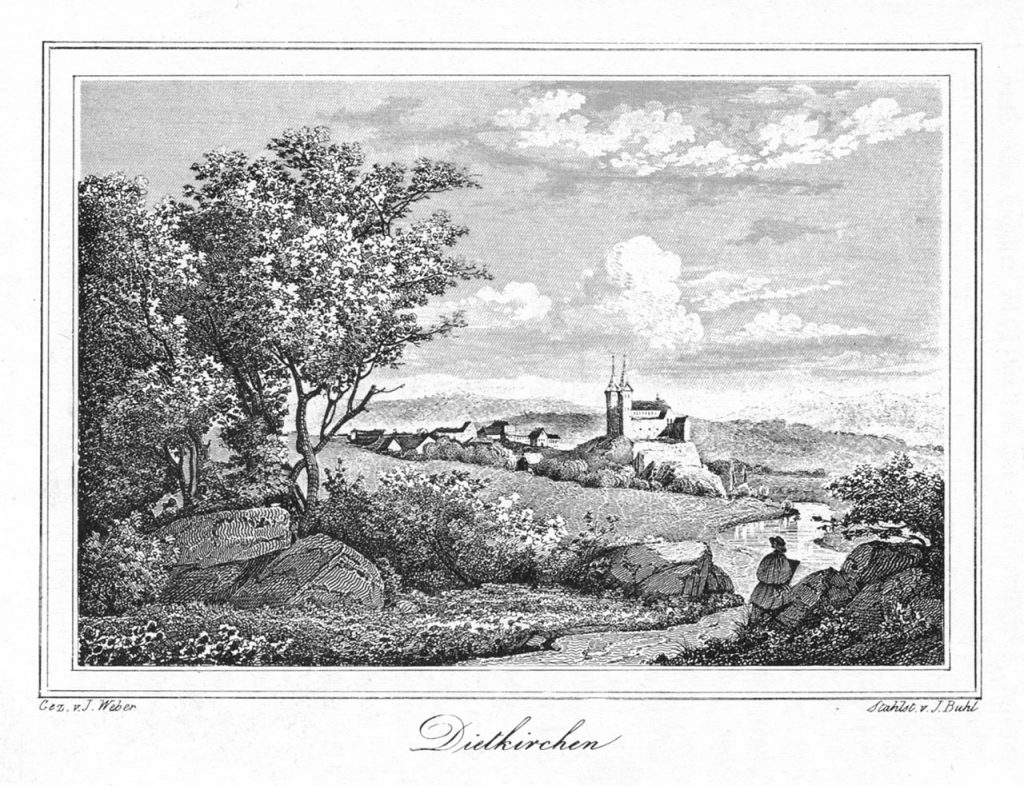

Picture from the yearbook for the diocese Limburg 1958

How did St. Lubentius get to Dietkirchen

The legend says that after Lubentius died in Kobern, nobody could move the sarcophagus in which his body should be buried. He couldn’t be moved. This was seen as a punishment for the fact that the Koberner disregarded his teachings and continued to practice their pagan rites and customs in part. Neither the priests nor bishops from Trier or Cologne, who had also come to Kobern to take Lubentius to their churches, were successful, the coffin could not be moved. After a long consultation, a judgment of God should then decide how to proceed. From that moment on the sarcophagus could be moved. The water should determine where the sarcophagus and body should go. The coffin was placed in a barge and pushed off the banks of the Moselle. From Kobern the barge then drove to the mouth of the Rhine, but from there it moved up the Rhine, past Koblenz and then drove into the Lahn until it landed in Lahnstein. There a woman is said to have given all of her property to Lubentius, and her sister, who did not want to give anything, is said to have fallen into a mental contempt. When the ship sailed up the Lahn the next day, her mental confusion had disappeared. The sister quickly crossed over to the other bank, where the ship had stopped again, and also gave Lubentius presents. According to legend, a holy spring arised from there that was named after Lubentius. The ship was then driven on until it landed 8 miles from the Rhine in Dietkirchen on the banks of the Lahn and did not move anymore from its location. According to legend, the pious men accompanying the ship on the bank, clerics and lay people, received the body and put him in the church on the rock for his last resting place while praising with hymns and psalms. The rock is said to have been shaken by an earthquake when it landed.

It was precisely at this grave that the St. Lubentius basilica was later built, in which the mortal remains of the saint have been documentedly kept from the 9th century to the present day.

Illustration from the yearbook for the diocese Limburg 1958

Sarcophagus of St. Lubentius in the church in Dietkirchen

Illustration from Wilhelm Schäfer, St. Lubentius zu Dietkirchen, p. 157, Wiesbaden 1966

The church St. Lubentius in Dietkirchen

Around 580, on the limestone rock in Dietkirchen a wooden chapel was erected in the form of a counterpart to the superstition, this chappel was replaced by a first stone church around 730 AD. The Stift (kind of a monestary) is most likely built between 830 and 838. The abbey has played an important role one to consolidate the Christian faith in the Lahngau, it was determined as the seat of the Trier archdeacon determined who directed the entire Trier’s right bank area of the Rhine. This remained the case until the abbey was dissolved in 1803.

The construction of the Today’s unique Romanesque church was started to build before the first millennium and completed in the 30s of the 13th century. The consecration day is probably the 1st Sunday after Oswald (05.08.) in the year AD 1225. This is how the parish fair is celebrated in Dietkirchen on the 1st Sunday in August.

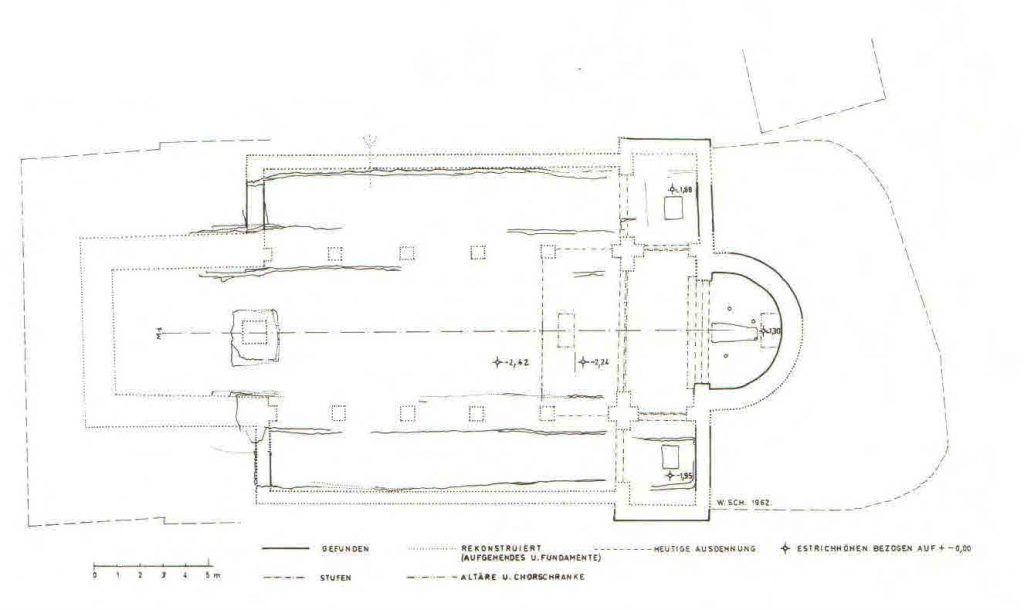

The research in the 50s and 60s of the 20th century showed the following structural building developments.

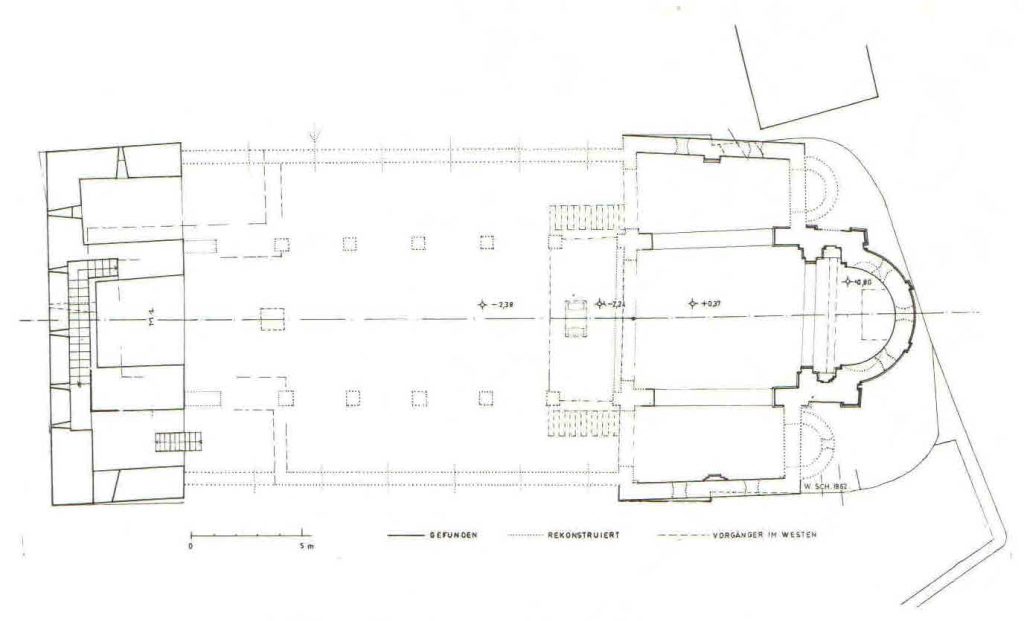

Church I

Hall church (Saalkirche) with drawn-in straight choir, an annex building in the north and south. The church is Merovingian or early Carolingian, probably around AD 730.

Church II

Three-aisled basilica with a narrow transept projecting by a walls thickness, light stilted middle apse, strong west tower (defense tower), which turns into the central aisle by opens in a double arcade. On the first floor of the tower there was probably a chapel room with an arcade opening to the aisle. The church is therefore Ottonian or early Salian, around AD 1000. Into this time the construction of the chapel of St. Michael is also dated. Enlargement of the abbey chapter. Burial of the abbey patron St. Lubentius in a brick crypt in front of the altar in the apse.

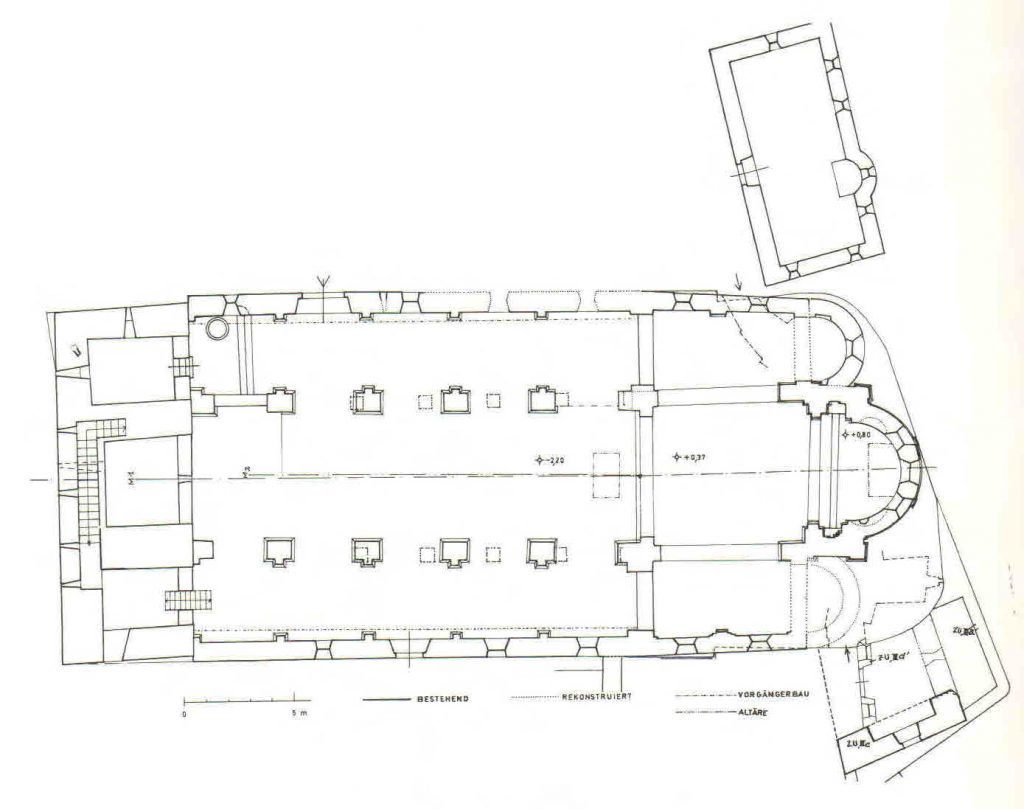

Church III

Church III consists of 4 building phases.

Church IIIa

Extension to the east and west to the steep edge of the rock. The eastern parts are standing on a massive substructure, in which a polygonal passage was created as a connection path from the north to the abbey buildings located to the south. The width of the church corresponded to Church II, the transverse nave was widened considerably and received a mid apse with a pre choir bay and two side apsids.

Church IIIb

Demolition and new construction of the long nave. Masonry of the to the nave opened arches of the two-tower system. Narrowing and increasing of the transverse nave, increasing of the mid apse. Completion of the tower front, tent roofs. Around 1100 or early 12th Century, early Hohenstaufen time.

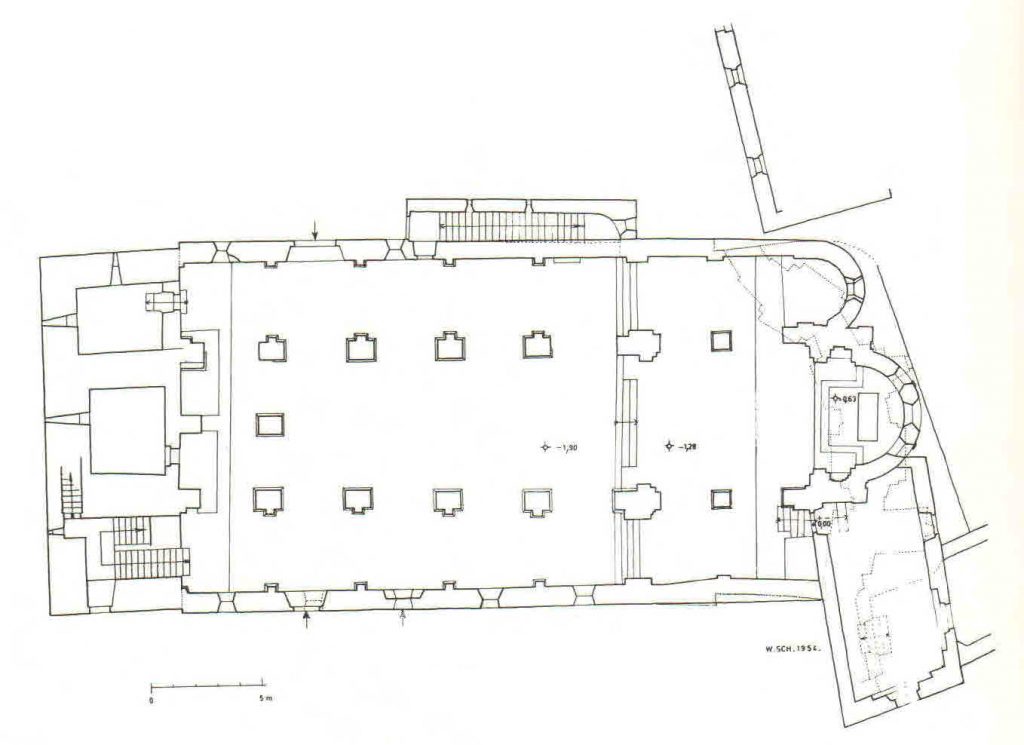

Church IIIc

Addition of real galleries and open western stone gallery. Raise of the flat ceiling and the upper storey of the long nave. Extension of a gallery staircase in the North. Conversion of the tower tent roofs to Rhenish diamond roof helmets, new construction of the sacristy in the 2nd half or third third of the 12th century.

Church IIId

Vaulting of the transept with the addition of two slender pillars. Demolition of the barrel vault of the so-called “crypt”. Arching of the sacristy. The Trinity Chapel is built. Around 1240 or 2nd quarter of the 13th century.

The first stone church, from which a limestone column of the 9th century still stands in the Diocesan Museum in Limburg was consecrated on 22 November 838, according to the mind of some documents. This, however, is not seen as such by one of the greatest connoisseurs of the monastery and the church history of St. Lubentius zu Dietkirchen, Wolf-Heino Struck. Quote from his book: DAS ERZBISTUM TRIER, Volume 4, DAS STIFT ST. LUBENTIUS IN DIETKIRCHEN:

“Provided that the consecration of the church took place on a Sunday according to regulations, however, 22 November at Dietkirchen Abbey cannot be brought into a safe connection with the first document of 841, the year 838 comes closest. But this consideration seems pointless, since the relationship of the November 22nd to the monastery, which Miesges (p. 115 note 2) assumes, is ruled out at all because of the proven church anniversary on the first Sunday after Oswaldi, unless one to assumes a change.”.

The foundation of the Lubentiustift therefore dates back to before 840. Relics of the saint rest in the Lubentius Chapel of the collegiate and parish church of St. Lubentius. The church of Dietkirchen is the only church in the diocese of Limburg in which relics of a male saint rest.

The archdeaconry was ranked second after Trier among the five Trier archdeaconates until 1778; it even ranked first from 1778 until its dissolution in 1803. In 1803 the parish counted about 425 parishioners who mostly were living off the monastry. The canons were the lords, which term today still lives on in the name “Herrnberg”.

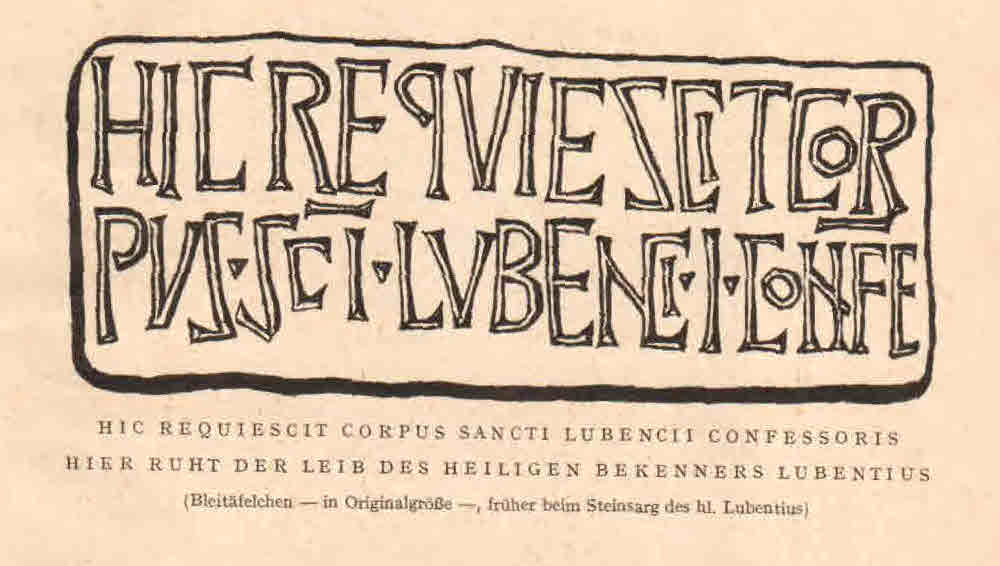

Ground plan of the church I

Illustration from Wilhelm Schäfer, St. Lubentius at Dietkirchen, p. 121, Wiesbaden 1966

Ground plan of the church II

Illustration from Wilhelm Schäfer, St. Lubentius at Dietkirchen, p. 121, Wiesbaden 1966

Ground plan of the church IIIa

Illustration from Wilhelm Schäfer, St. Lubentius at Dietkirchen, p. 121, Wiesbaden 1966

Ground plan of the church IIIb

Illustration from Wilhelm Schäfer, St. Lubentius at Dietkirchen, p. 122, Wiesbaden 1966

Ground plan of the church after 1885

Illustration from Wilhelm Schäfer, St. Lubentius at Dietkirchen, p. 122, Wiesbaden 1966

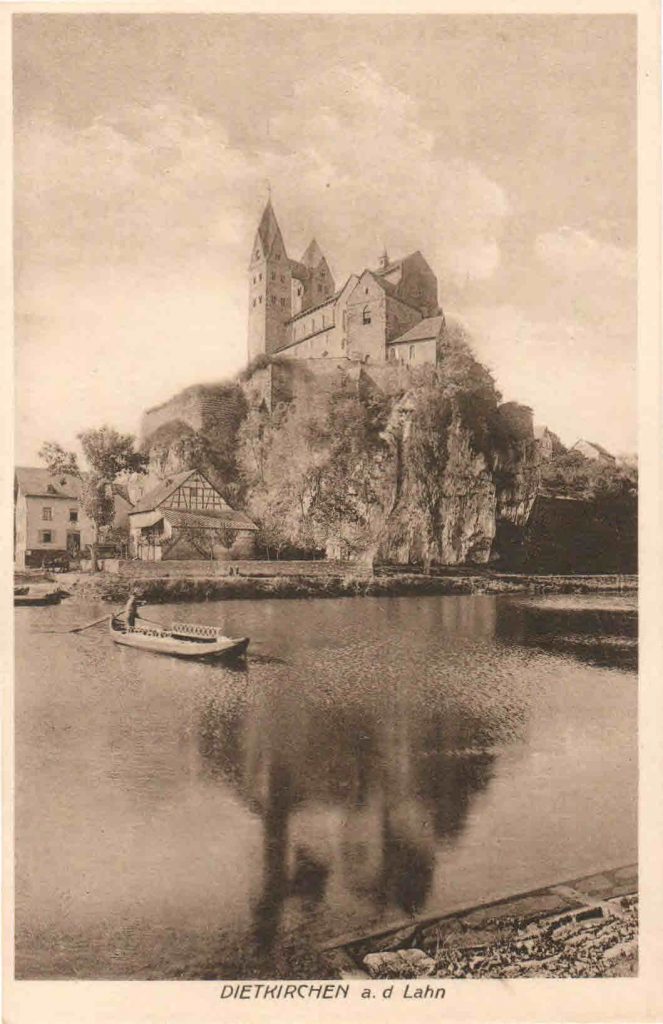

Lahn ferry (probably between 1940-1950s)

Collection Ludwig Ries

Lahn ferry

In the past centuries, the Lahn ferry in Dietkirchen had an important task. It is mentioned in a document of the monastery provost Rambert, who is documented as archdeacon between 1084 and 1098. During this time he enfeoffed the brothers Rembold, Wolfhart and Gerhard with the ferry of Dietkirchen. By the way, this document is the oldest document of the monastery of Dietkirchen available in copy. The importance of the ferry is also emphasized by this document.

The main task of the ferry service was the carrying of the parishioners and other passengers living beyond the Lahn. The parish included the faithful from Mühlen, Eschhofen, Lindenholzhausen and Dehrn. As can be seen from later documents, the ferryman’s duties consisted in ensuring that the ship, the rope and all the utensils belonging to the ferry were kept in good order. Furthermore he has to transfer the clergy from one shore to the other as often as necessary. If the Holy Sacrament is required on the other side of the Lahn, the ferryman must be available by day or night.

In 1959 the ferry service was discontinued, in 1976 it was reactivated again by the city of Limburg. Due to technical problems of the ferry, however, the operation was finally stopped in 1980. As a replacement, a 145 metre long and 3.30 metre wide wooden cycle and foot bridge was inaugurated on 29 October 1989, making an old dream of Dietkirchen and the villages on the other side of the Lahn come true.

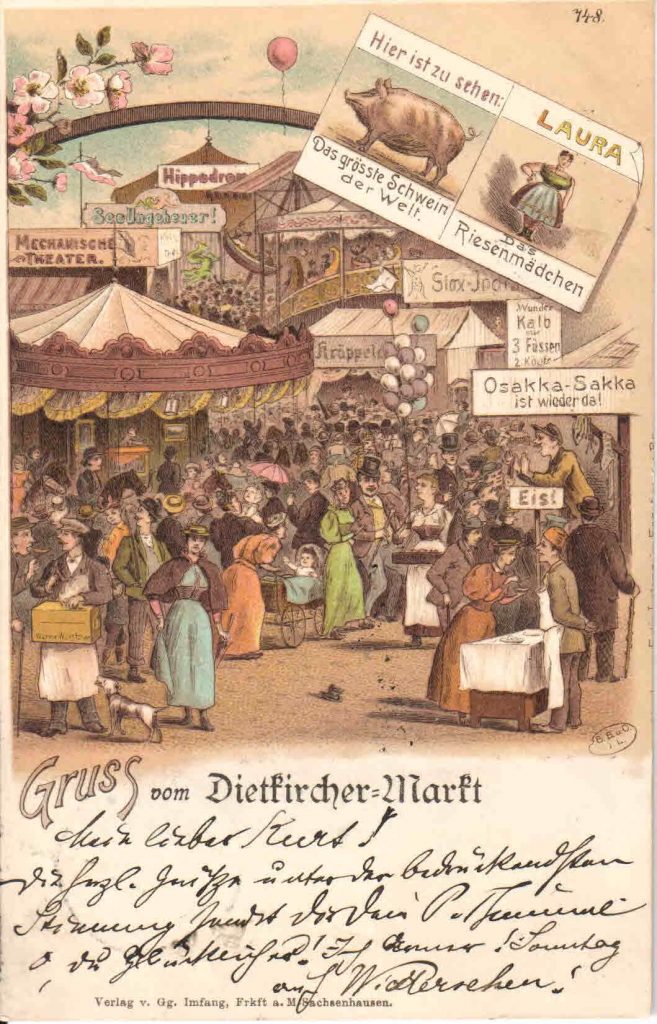

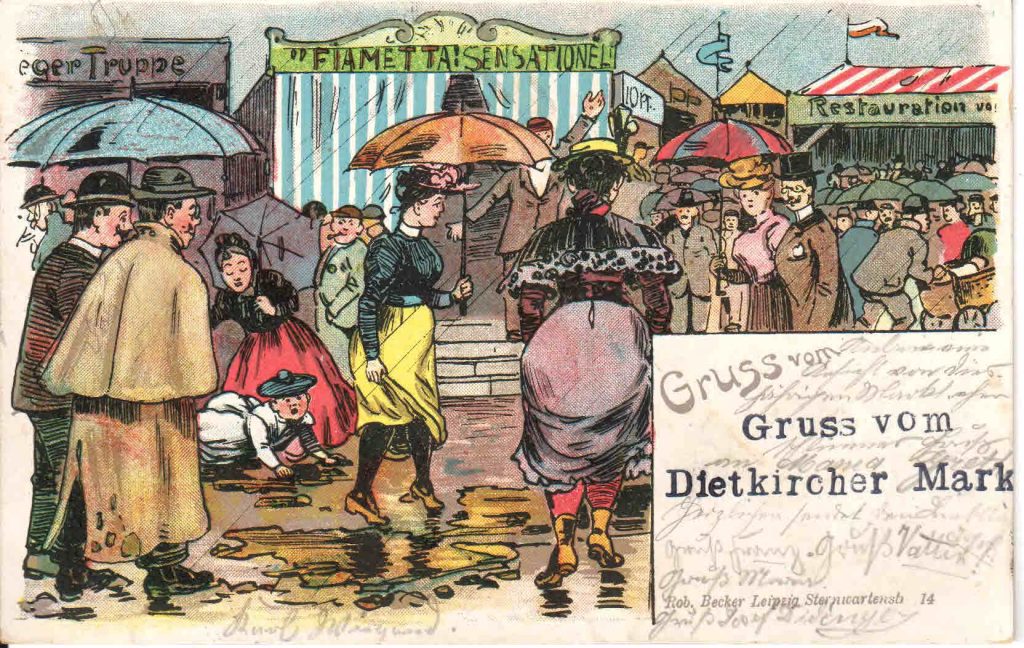

Dietkirchen Market

The Dietkirchen market also belongs to the local history. The market on Lubentius Day was first documented in 1538, the first beginnings cannot be dated, but it is assumed that the market was held as early as the 13th century on St. Lubentius Day on 13 October (see Wolf-Heino Struck, Von den Jahrmärkten auf dem Westerwald, Nass. Annals 1962). The origins of the market are therefore probably in the High Middle Ages. For example, there is a reference in the Limburg town book of 1548, which states that as early as 1378, traders at the Limburg Michaelis market and also those who visited the Dietkirchen market were guaranteed free convoy (Marie Luise Crone, Dietkirchen, 1991).

The market was distinguished as a cattle, junk and flax market and was one of the “main markets in the Kurtrierian areas”. Visitors from near and far used to come to the market. In 1773, a total of 101 tradesmen are said to have supplied the market: 2 iron workers, nail smiths and white tanners, 7 stocking weavers and butchers, 11 wool weavers, 14 innkeepers, 27 shopkeepers and 28 bakers. Towards the end of the 17th century the market is said to have reached its peak. Thus 4-5 beer landlords, 10-12 butchers or cooks, 24 bakers and 28-30 wine landlords were active on the market. There is no evidence of the number of craftsmen represented, but it can be assumed that there were also a large number of them who enlivened the Dietkirchen market, as the Westerwald markets were generally very busy with shopkeepers and craftsmen (see Wolf-Heino Struck, Von den Jahrmärkten auf dem Westerwald, Nass. Annals 1962).

In the middle of the 30s of the 20th century, the National Socialist organisation “Kraft durch Freude” (Strength through Joy) set up a massive counter-event in Limburg to push the Dietkirchen market into the background. The Limburg event was held on the same day as the Dietkirchen market. This event then led to the displacement of the Dietkirchen market, both in the 1930s and through its return after the war years, so the market finally came to an end in the 1950s/60s.

Since 1991 the Dietkirchen market has been revived by the 3-year orientation of a “Historical Dickerischer Market” (Historischer Dickerischer Maat), organized and carried out by the Dietkirchen associations.

Postcard from Dietkirchen Market

Postal stamp 06.10.1898

Collection Ludwig Ries

Postcard from Dietkirchen Market

Postal stamp 04.10.1900

Collection Ludwig Ries

La Pendaison (The Hanging), Jacques Callot (1632).

The picture shows the execution of thieves and probably also marauders throwing dice for their lives (in the picture on the right). The measure is not an arbitrary act, but is carried out in the presence of clergymen and corresponds to the martial law of the time, to maintain military discipline.

Source:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacques_Callot,_The_Hanging,_c._1633,_NGA_51931.jpg

Irish high cross on the prison cemetery of the I. World War

Wars

The village was not spared from warlike events in the past centuries.

During the Peasant Wars in 1524/1525, for example, the monastery was plundered by residents of the neighbouring community of Dehrn.

Also during the 30 Years War (1618-1648) there were impairments due to plundering and billeting. There are reports of major fire damage to the monastery church roof and also of the devastation of 2 monastery houses on the south side of the church. Most of the canons themselves probably went into exile during this time and thus left the place spiritually alone (Wolf-Heino Struck, Das Stift St. Lubentius in Dietkirchen, page 71).

This war also seemed to have had lasting effects on the clergy, since it is reported that Archbishop Karl Kaspar von der Leyen made an extraordinary visit to the monastery on April 29, 1662, when it was declared with a fine of 2 gold florins that the canons had to beware themselfes in future not to visit the taverns (popinas) in Limburg and to sit together there with players and other scandal makers (Wolf-Heino Struck, Das Stift St. Lubentius in Dietkirchen, page 71/72).

During the First World War, a prisoner of war camp was established near Dietkirchen, where up to 12,000 prisoners of war lived. Even today, there is still a war gravesite near the former camp, where many deceased prisoners of war were buried. Dietkirchen had 13 dead fellow citizens and 2 missing person to mourn.

The Second World War also brought sorrow and suffering to Dietkirchen. In the end there were 46 dead and 26 missing from the village. Pastor Wilhelm Breithecker, who came to Dietkirchen as a pastor on February 1, 1939, was arrested on March 7, 1939. Via prison wards in Kassel, Halle and Berlin Alexanderplatz he was sent to the Sachsenhausen Oranienburg concentration camp in 1940. In November 1940 he and other clergymen were transferred to Dachau, where he remained until his release on March 28, 1945.

District of Limburg

In 1971 the municipality gave up its independence and was the first of the surrounding villages to be incorporated by the city of Limburg.

As of September 2019, the Dietkirchen district has 1,724 inhabitants (source: www .limburg.de, 27.12.2019).

There is certainly much more to find out about the village of Dietkirchen, some of which is certainly still in hidden sources at the moment.

Sources:

- Mrs. Dr. Marie-Luise Crone, Geschichte eines Dorfes im Schatten des St. Lubentiusstiftes Dietkirchen (ISBN-Nr 3-9802789-0-5)

- Peter Paul Schweitzer, Reckenforst, 2005, https://ippsch.de/index.php/erforschtes/oertlichkeitsnamen-im-kreis-limburg-weilburg

- Wolf-Heino Struck, Das Stift St. Lubentius in Dietkirchen, 1986, Walter de Gruyter – BERLIN – NEW YORK

- Wolf-Heino Struck, Von den Jahrmärkten auf dem Westerwald, Nass. Annalen 1962

- Karl Wurm in in Wilhelm Schäfer: Die Baugeschichte der Stiftskirche St. Lubentius zu Dietkirchen im Lahntale, 1966, Selbstverlag der Historischen Kommission für Nassau

- Karl Wurm, Vorbericht über die Abschlußgrabung unter der Stiftskirche von Dietkirchen/Lahn im Sommer 1965, in “Fundberichte aus Hessen, 5. u. 6. Jahrgang, 1965/66, Verlag Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn”